|

Angels: so what?

29th September 2002, Michaelmas

Genesis 28:10-17; Revelation 12:7-12; John 1:47-51

Well,

what are we to make of angels? Here we are making a bit of a song and

dance (well OK, not a dance - not quite at St Peter's) about the feast of St

Michael and all Angels, but why? Well, traditionally it has been an

important day in the year both for the church (ordinations have

traditionally taken place at this time) and for the secular world (Michaelmas

being one of the quarter days when rents and tithes and all that were paid,

and of course the law term is still known as Michaelmas). My curacy was

served in a church and a town dedicated to St Michael, and we made

opportunity for church and town to come together to celebrate, decorating St

Michael's Pant (that's Northumbrian for water pump, if you were wondering)

and organising jamborees of all sorts with the schools and other churches,

and the Mayor in her finery. Plenty of stuff for sermons; but not really

getting to the heart of the problem of angels.

Well,

what are we to make of angels? Here we are making a bit of a song and

dance (well OK, not a dance - not quite at St Peter's) about the feast of St

Michael and all Angels, but why? Well, traditionally it has been an

important day in the year both for the church (ordinations have

traditionally taken place at this time) and for the secular world (Michaelmas

being one of the quarter days when rents and tithes and all that were paid,

and of course the law term is still known as Michaelmas). My curacy was

served in a church and a town dedicated to St Michael, and we made

opportunity for church and town to come together to celebrate, decorating St

Michael's Pant (that's Northumbrian for water pump, if you were wondering)

and organising jamborees of all sorts with the schools and other churches,

and the Mayor in her finery. Plenty of stuff for sermons; but not really

getting to the heart of the problem of angels.

So, I wonder whether I should carry out a little opinion poll? Do angels exist? Don't worry, I won't ask for hands to be raised - it might put some on the spot. We have a major festival that says they do. The Bible tells us pretty firmly they do. Artists and hymn writers and poets, and those who holy people who paint icons are quite sure they do. And much popular religious faith believes they do. But intellectually, at this point in the twenty-first century, what do we think? Ah, drop "Hark the Herald Angels sing" from the Christmas festivities and you're in trouble. Question from the pulpit the historical truth of the stories surrounding the birth of Jesus, and you become an outcast - because the task of the preacher in the popular mind is to reassure not to cast doubt.

If I were to ask how many of you have seen an angel, I know there would be some who would say yes. We want to believe it; we want to be assured that we are enwrapped in the loving protection of a guardian angel - but doubts niggle away. As the world develops, and science uncovers more and more, and technology puts within our grasp methods of communication which 100 years ago could only have been achieved by angels, it is all so much more complicated. Indeed, one might argue, the whole structure and content of religious faith becomes much more controversial and difficult to defend. And the end result of that is that the church loses confidence in its fundamental message; which is a message about God, about creation, about redemption, about the eternal faithfulness and love of God for all people, all creation, the God who was, who is, who is to come, and who, through Jesus his Son, is intimately involved in every aspect of the life of that which he has created and continues to create. That message is, literally, awesome. But we are drawn instead into the desert of puerile argument about whether this bit or that bit of our faith, or the Bible is literally true, about whether this person or that person in their behaviour is acceptable to God, about whether how we used to do it was better than how we do it now. I want to cry out at the Church - and that is as much to myself as to anyone else - "Look up!" Look up, look out, a vision of God is there for the taking, but while we are bickering away about trivialities, the world of which we are stewards is clouding over. There is a terrible failure of the imagination. We are becoming monochrome, introverted and superficial. The vision of the glory of God and his creation, which is what we claim to offer to the world, is vapid and effete, and we too often lack the basic courage to live what we believe.

Now before any more whispers start up about where I am coming from, or the direction in which I am trying to lead the parish, let me clarify what it is I am trying to say in the context of this feast of Michaelmas. The history of the institution of the church and its relationship with the people who consider themselves to be members is fraught with difficulties. It is in many ways an unhappy history. From the fourth century, when Constantine declared Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire, things changed fundamentally. The Church got into the power game. Sometimes it wielded power for good and sometimes for not so good. But that it was powerful was without question. So there was, from that moment, a fundamental tension in the life of the church - between the message of the Gospel and the role in society that clergy and religious found themselves playing. In a world lacking in education, clergy taught. In a world of poor health and short lives, monks and nuns nursed. In a world of greed and cheap political violence, bishops and popes held the strings of international power and influence in a vice-like grip. And theology and church practice developed accordingly; so the medieval church, grasping and corrupted in some places, produced great holiness and vision at the same time. Francis of Assisi and Catherine of Siena and many others held one end of the rope while others in Rome and Avignon and even Canterbury pulled on the other.

The theologians of Germany and Switzerland and Britain in the 16th Century finally gained sufficient influence within the church, and support from their national rulers, to challenge what they decided was the wholesale corruption of the church. They swept away the medievalism, the superstition, the papal power, the corruption - but they forgot (if ever they knew) the warnings about babies and the bath water. Of course they never really got to the heart of the issues about power, because they were quite keen to exercise power too (and in England, the changing demands of various monarchs required quite a bit of flexibility on their part). And they forgot about the holy people and their vision, nurtured through that selfsame church.

Have you been to San Gimignano in Tuscany, to the Collegiate Church there - or indeed to many of the churches in Florence and Siena? Of course, after eight days there I am now an expert, and I certainly saw more than a few angels during our travels. But to walk into that amazing church, the walls covered in the most wonderful 14th century frescoes, telling the stories of the Old Testament and of Jesus, to go into the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, into the 12th, 13th and 14th century rooms; is to be completely floored by the Giotto altar-pieces, and those of his pupils. The images are imaginary. No-one reading the Bible could come up with pictures so rich and profound without the insight of imagination, an imagination used entirely in the service of God. Colour, beauty, great artistry. And one sits before them and drinks this glory in, and one cannot but be drawn into prayer - prayer of adoration, of thanksgiving, and just pure, silent contemplation. The Reformation would have covered all that up in a fit of pious, indignant puritanism, and our ten year old companion for the day, who has little by way of faith, but is rich in imagination, would have missed an education.

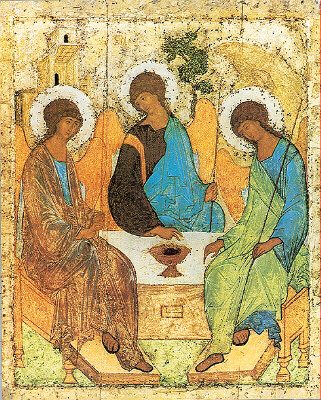

Music, silence, incense, colour, communion - all these engage our senses in a journey of imagination which can open up our conversation with God in new and wonderful ways. As Henri Nouwen the very popular Roman Catholic writer, now sadly dead, writes in his meditation on the Rublev Icon which we have here in front of us:

The Russian mystics describe prayer as descending with the mind into the heart and standing there in the presence of God. Prayer takes place where heart speaks to heart, that is, where the heart of God is united with the heart that prays.

Can you not almost see in those words that vision of Jacob, echoed by Jesus, of angels ascending and descending between the heart of God and of his people? We have no reason to be frightened of the imagination. We need to see, to hear, to touch, to taste that our whole heart may be opened up to the vision of God. To prevent this sensuality, to forbid the use of all our imagination in our search for God is to emasculate (forgive the gender specific word) that search. To be faithful witnesses for God today we need so much more than a cold intellectual assent to the doctrines and scriptures we have inherited. We need vision. We need engaged hearts.

A friar writing at much the same time as those frescoes were being painted in Tuscany, wrote:

The gloom of the world is but a shadow; behind it, yet within our reach is joy. Take joy.

We stand, as people of faith, on the cusp of that vision which our world today is crying out for. Someone famous said "All war is a failure of the imagination". The cloud which is forming over the Middle East is precisely that - a failure to see that there is any other course than to use power and force to achieve one's aims. The true disciple has a challenge, even an answer to that. The vision of a world and a humanity infused with God, a world which may seem to be burdened with gloom but is in actuality suffused with joy and life and love. Rublev's icon, there, is a prayer of invitation to join the angels in a community of love. It too is from the fourteenth century and, as Henri Nowen says again:

Fear and hatred have become no less destructive since the 14th century, and Rublev's icon has become no less creative in calling us to the place of love, where fear and hatred no longer can destroy us.

Do not be afraid. Be fully human. Be confident in God's faithfulness and love. And pray with all your heart. And the angels, whether you see them or not, will unite your heart with the heart of God. And who knows what then might happen?

Return to the Logoi contents page

http://www.stpetersnottingham.org/sermon/angels.html

© St Peter's Church, Nottingham

Last revised 7th November 2002