|

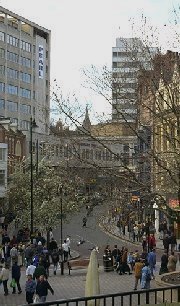

Nottingham, the City

The elegant modern city which we know as Nottingham evolved from

the ancient settlement of Snotingaham - the "ham" or home of the followers of a

Saxon bearing the unfortunate name of Snot. The site of this settlement can still be

located in Nottingham today: it was centered around the present St Mary's Church and

covered about 39 acres in the area which achieved fame in later centuries as the Lace

Market.

The elegant modern city which we know as Nottingham evolved from

the ancient settlement of Snotingaham - the "ham" or home of the followers of a

Saxon bearing the unfortunate name of Snot. The site of this settlement can still be

located in Nottingham today: it was centered around the present St Mary's Church and

covered about 39 acres in the area which achieved fame in later centuries as the Lace

Market.

Norman times - two boroughs

By the time of the Norman Conquest, Nottingham had developed into a semi-agricultural town with a population of between 600 and 1,000. We can only imagine the anxiety which the violent events associated with the Norman invasion must have caused these people, but fortunately a rocky ridge, well to the west of their borough, was chosen by William the Conqueror as the site of the wooden fortress which he built in 1067/68; so the Saxons were spared the loss of houses and property rights which so often accompanied castle building at this time. William placed the castle in the custody of his illegitimate son William Peverel. A Norman borough grew up in the shelter of the Castle, leaving the Saxons largely undisturbed in their borough on St Mary's Hill. This situation gave rise to Nottingham's twin French and English boroughs with their different legal customs.

Nottingham becomes established

Over the following centuries, the wooden castle was rebuilt in stone and its fortifications and accommodation were improved. Politically, Nottingham Castle represented the base of the King's power in the Midlands and North, as it controlled the bridge over the River Trent, where a major road to the north crossed the river. Socially, the castle was a favourite royal residence throughout the medieval period as it provided access to Sherwood Forest for hunting. Indeed it was from Nottingham that Richard III rode out to meet the army of Henry Tudor, and his own death, on Bosworth Field in 1485.

Under Norman protection, Nottingham's twin boroughs became firmly established. In 1155 the town was granted a Charter by Henry II, which recognised it as an ancient borough and granted it the privilege of holding a market on Fridays and Saturdays for traders from Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. This market quickly became a focal point of town life. At certain times of the year, often coinciding with pilgrimages or local festivals, it would become a fair, attracting people into the town from far and wide.

In 1449, a century after the ravages of the Black Death, Nottingham's resident population had risen to about 3,000, a sizeable number for those times. It was in this year that Henry VI granted the town its Great Charter, elevating it to "Town and County of the same Town", making it independent of the County Sheriff and subservient only to the King.

The knitting frame

In the sixteenth century a machine was invented which was to alter the face of Nottingham industry in the centuries to come, and one which was to play a central role in the industrial unrest of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. That machine was the knitting frame, invented by the Calverton curate William Lee in 1589. According to a popular story, Lee was courting a girl who was so passionately fond of knitting that it claimed more of her time than he did. In order to rid himself of his rival, Lee set about developing a machine that would allow the knitting to be done mechanically. Unfortunately, exploitation of Lee's innovation was delayed for many years, as Queen Elizabeth I refused to grant it royal patronage for fear that it would threaten the livelihood of the hand-knitters. Lee took his invention to France, but after his death in 1610 some of the machines were brought to England and sold in London. Some probably found their way to Nottingham, as the framework-knitting industry started here in the middle of the seventeenth century, without the royal patronage which Lee had regarded as essential.

Great events

Two

major national events of this period were remembered when a former Nottingham man, Luke

Jackson, made his last will and testament in October 1630. Luke, son of Anker Jackson, a

churchwarden of St Peter's, was apprenticed to a girdler in London. Luke obviously never

forgot his early life in Nottingham or his association with St Peter's Church, as among

his bequests was a requirement that the Rector of that church should preach two charity

sermons annually: one to commemorate the defeat of the Spanish Armada in July 1588 and the

other to give thanks for the country's deliverance from the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. These

events, both falling within the first twenty-five years of Luke Jackson's life, must have

made a tremendous impact on the life of everyone in the country, arousing great fear

followed by great relief, and it is not surprising that he wished to commemorate them.

Two

major national events of this period were remembered when a former Nottingham man, Luke

Jackson, made his last will and testament in October 1630. Luke, son of Anker Jackson, a

churchwarden of St Peter's, was apprenticed to a girdler in London. Luke obviously never

forgot his early life in Nottingham or his association with St Peter's Church, as among

his bequests was a requirement that the Rector of that church should preach two charity

sermons annually: one to commemorate the defeat of the Spanish Armada in July 1588 and the

other to give thanks for the country's deliverance from the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. These

events, both falling within the first twenty-five years of Luke Jackson's life, must have

made a tremendous impact on the life of everyone in the country, arousing great fear

followed by great relief, and it is not surprising that he wished to commemorate them.

The Civil War

When we think of the seventeenth century, the Civil War between King and Parliament springs immediately to mind. Although Charles I raised the Royal Standard in Nottingham on 22nd April 1642 to rally support the town remained loyal to Parliament throughout the conflict, though it did not have an important role to play. There were however skirmishes between the troops of the Nottingham garrison and those of the Royalist stronghold of Newark. Most of the Royalist attempts to gain entry into Nottingham were foiled, but one night in September 1643 they were successful in entering the city. They seized St Nicholas' Church, the steeple of which provided an excellent vantage point for firing on the castle. The troops managed to hold out there for five days before being driven off, after which Colonel John Hutchinson, who held the castle, pulled the church down. It was not rebuilt until 1682, and until that time its congregation worshipped in St Peter's. The Duke of Newcastle offered Hutchinson the gift of the castle and £10,000 if he would switch his allegiance to the Royalist cause, but Hutchinson was not to be tempted and replied, in true fighting spirit, that if the Duke wanted the castle he would have to wade to it through his own blood. In 1651 after the war had ended, much of the castle was destroyed by the Parliamentarians. The ruins were cleared away by the first Duke of Newcastle who, with his son, built a ducal palace on the site. This building survived until the Reform Riots of 1831.

War in America

Through Sir William Howe, who was MP for Nottingham from 1758 to 1780, the city has links with North America in one of the most dramatic periods of its history. Howe, one of the family of Langar, fought in America during the Seven Years War, playing a leading role in the capture of Quebec in 1759, when he led a party of men up a goat path to scale the Heights of Abraham. He returned to the continent after the outbreak of the American Revolution, when he led the British troops to victory at Bunker Hill in 1775 and was promoted Commander-in-Chief in 1776. He resigned after the defeat of Saratoga in 1778. On his return he resumed his political career, later succeeding his brother as Viscount Howe. His successor as MP for Nottingham was Robert Smith, later the first Lord Carrington, several of whose family are buried in St Peter's.

The Luddites

The Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century is, for Nottingham, the period associated with the Luddite riots among the stockingers. New machinery and changes in production methods were seen by many as a threat to their livelihood: in those days of low wages and the ever-present threat of actual starvation should those wages stop for any reason, these innovations must have made the prospect even more gloomy. Not unnaturally the stockingers rioted, breaking into hosiery factories and smashing with sledgehammers the knitting frames which they blamed for their plight. The rioters earned the name of "Luddites" as they would give written notice of their intentions, signed "Ned Ludd". (Ned Ludd was supposedly a Leicestershire youth who smashed machinery in 1799.) There were serious outbreaks of Luddism in Nottingham in 1811, when food shortages resulting from the Napoleonic Wars and high unemployment, exacerbated the desperation of the stockingers.

Happily, a short period of prosperity was enjoyed around 1823, when Heathcoat's patent for adapting the stocking-frame to make lace expired. Nottingham quickly developed into the largest lace-making centre in the world. In sharp contrast to the situation only a few years earlier, profits were now shared by machine-owners and workforce alike, and prices and wages were the highest Nottingham had ever known. This happy state of affairs was short-lived however, as supply soon outstripped demand, bringing ruin to many.

Reform Riots

In the abject poverty and atrocious living conditions of the

nineteenth century, people set great hopes for improvement on the Government's Reform

Bill, drafted in 1831. Rejection of the Bill by the House of Lords was the cause of the

Reform Riots, which broke out in October 1831. The riots lasted several days, despite

troops being called in. Rioters rampaged through the town, tearing down railings for

weapons and destroying mills and property. The Castle was pillaged, tapestries being torn

up and sold to bystanders for 3 shillings a yard. The burnt-out castle remained a roofless

ruin for over forty years before it was restored and started a new life as England's first

municipal museum and art gallery. (The first curator of the museum, G.H. Wallis, was

churchwarden at St James', where he commissioned a charming memorial to his daughter

Catherine, now in the north aisle of St Peter's.

In the abject poverty and atrocious living conditions of the

nineteenth century, people set great hopes for improvement on the Government's Reform

Bill, drafted in 1831. Rejection of the Bill by the House of Lords was the cause of the

Reform Riots, which broke out in October 1831. The riots lasted several days, despite

troops being called in. Rioters rampaged through the town, tearing down railings for

weapons and destroying mills and property. The Castle was pillaged, tapestries being torn

up and sold to bystanders for 3 shillings a yard. The burnt-out castle remained a roofless

ruin for over forty years before it was restored and started a new life as England's first

municipal museum and art gallery. (The first curator of the museum, G.H. Wallis, was

churchwarden at St James', where he commissioned a charming memorial to his daughter

Catherine, now in the north aisle of St Peter's.

Cholera

The appalling overcrowding of the workers' back-to-back housing and the lack of sanitation meant that, even in the nineteenth century, cholera still had Nottingham firmly in its grip. There were outbreaks of the disease in 1832, 1848, 1853 and 1865. In the 1832 outbreak 1,110 cases were recorded, of which 289 proved fatal. The seriousness of this epidemic resulted in the establishment of a Board of Health, the chairman of which was Thomas Wakefield, a prominent member of the Corporation. Wakefield demonstrated his concern for the victims by visiting them in their slums, with little regard for his own safety. Thomas Wakefield was the son of Francis Wakefield, a notable philanthropist who did much to improve the lot of Nottingham's poor in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Francis was an active member of the congregation of St Peter's, and held every church and parish office over the period 1784-1818.

Enclosure Acts

The main reason for the overcrowding was the common-land status of much of the area outside the old city walls - roughly, north of Parliament Street and south of Canal Street. That meant the land could not be built on, and more and more people had to crowd into the existing urban area as they were attracted by work in the new industries of the early nineteenth century. Not until the middle of the century was it possible for the Town Council to have Enclosure Acts passed, to allow the development of the Sand Hills to the north and the Meadows to the south and so to relieve in part the hideous slums.

At the same time efforts to improve sanitation began to affect the public health of Nottingham, so long a prey to disease and epidemic. This was seen throughout England, as new ideas and ideals came flooding into the life of the nation, giving people the hope of decent housing, clean water, and clean air to breathe.

Cities and Cathedrals

Nottingham's Roman Catholic Cathedral on Derby Road, designed by Pugin, was built as St Barnabas' Church in 1841-44 (it became a cathedral in 1851), though Nottingham did not officially attain City status until 1897. In that year of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, it was elevated in status from "Town and County of that Town" to "City and County of that City", in recognition of its great achievements. By then, the Anglican diocese of Southwell had been set up, in 1884 when Southwell Minster rather than a church in Nottingham was chosen as the seat of the bishop. (Until then, Nottinghamshire had for centuries been in the diocese of York, and for a shorter period under Lincoln.)

The twentieth century begins

The early years of the twentieth century, mainly after

the First World War, saw major slum clearance programmes and improvements in sanitation.

The Council House, designed by Cecil Howitt, which with the great bell which chimes away

the hours dominates the City Centre today, was built on the site left vacant after razing

the old Exchange. Some of the white facing stone used in the building is said to have been

originally destined for St Paul's Cathedral in London. It had been cut and dressed but

was not used, and so remained untouched in the quarry for over 200 years. The completed

building was opened by the then Prince of Wales on 22nd May 1929. A covered

market was opened in Nottingham in 1928 and in the same year the Goose Fair moved from the

Old Market Square to its new site on the Forest. The stage was now set for the development

of modern Nottingham.

The early years of the twentieth century, mainly after

the First World War, saw major slum clearance programmes and improvements in sanitation.

The Council House, designed by Cecil Howitt, which with the great bell which chimes away

the hours dominates the City Centre today, was built on the site left vacant after razing

the old Exchange. Some of the white facing stone used in the building is said to have been

originally destined for St Paul's Cathedral in London. It had been cut and dressed but

was not used, and so remained untouched in the quarry for over 200 years. The completed

building was opened by the then Prince of Wales on 22nd May 1929. A covered

market was opened in Nottingham in 1928 and in the same year the Goose Fair moved from the

Old Market Square to its new site on the Forest. The stage was now set for the development

of modern Nottingham.

Local history web pages

Index of the

Past. The Nottingham Hidden History Team

Trent & Peak

Archaeological Trust. Archaeological research in Nottinghamshire and

Derbyshire

Return to the History contents page

http://www.stpetersnottingham.org/history/city.htm

© St Peter's Church, Nottingham

Last revised 5th November 1997