|

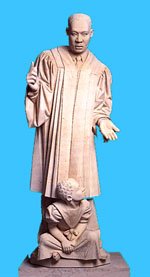

Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-68)

4th April

One of the Christian Martyrs commemorated by the erection of a statue on the west front of Westminster Abbey in 1998

Many

of us will have grown up with the doctrine: ‘Judge a person by their

heroes’. The danger with heroes is that their impact on us can diminish

with time - either undermined by sceptical even cynical re-evaluation, or

simplified, stripped of the ‘hard edges’ that we find too challenging

and prefer to gloss over, forget or ignore. Twentieth Century martyrs can

be particularly uncomfortable, tempting us to search their boots for clay

(overlooking our own) or seek other ways of diluting the challenge they

present.

Many

of us will have grown up with the doctrine: ‘Judge a person by their

heroes’. The danger with heroes is that their impact on us can diminish

with time - either undermined by sceptical even cynical re-evaluation, or

simplified, stripped of the ‘hard edges’ that we find too challenging

and prefer to gloss over, forget or ignore. Twentieth Century martyrs can

be particularly uncomfortable, tempting us to search their boots for clay

(overlooking our own) or seek other ways of diluting the challenge they

present.

Martin Luther King is a hero to many, and a good example of this ‘sanitisation’. A campaigner for civil rights, he has buildings and streets named after him in many parts of the world, and his picture has appeared six times on the cover of Life magazine. Yet whom do we honour? Writing twenty five years after his death Julian Bond wrote in the Seattle Times:

Today we do not honour the critic of capitalism, or the pacifist who declared all wars evil, or the man of God who argued that a nation that chose guns over butter would starve its people and kill itself. We do not honour the man who linked apartheid in South Africa and Alabama; we honour an antiseptic hero. We have stripped his life of controversy, and celebrate the conventional instead.

Born in Atlanta in 1929, Martin Luther King was raised in the vibrant and confident tradition of African-American Christianity, the son and grandson of Baptist preachers, and was himself ordained at the age of 19. After a broad education he was awarded a BA from Moorhouse College, followed by a Bachelor of Divinity from Crozier Theological Seminary, and went on to complete a PhD in systematic theology at Boston University.

As a boy he lived daily with the humiliations of segregation, exclusion, violence and racial hatred. In Boston he matured in a more accepting and intellectual climate among people from all backgrounds. In 1953 he began a secure and loving family life with his marriage to Coretta Scott.

Martin’s entry into public life, as preacher at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery in 1954, was not as a firebrand rebel but a mild-mannered man who even found some forms of religious expression in his own tradition, “shouting and stamping”, too emotionally boisterous - including in his own father’s church.

With an inquiring nature, he was constantly searching for ways to link the gospel to the life he found around him and continually questioning the depths of his own faith. His social gospel approach insisted that Christians “must do more than pray and read the Bible” - society as well as individuals needed redemption. He was a politically concerned preacher rather than an activist, his speeches visionary rather than incendiary.

In December 1954 Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery to a white passenger and was arrested for violating city and state laws. Although not the originator, Martin became leading organiser of the year-long boycott of city buses by the black community which only ended when the US Supreme Court declared those segregation laws unconstitutional. His youth, professional status and training made him effective, while his skills as an orator and personal courage brought him to national attention. His home was bombed, his family insulted and threatened, local police were assigned to uncover ‘all derogatory information’ about him, and he was imprisoned for speeding (at 30mph in a 25mph zone).

Martin was a lifelong admirer of Ghandi and his spiritual approach to non-violent confrontation. This was his way too, with the ultimate goal of reconciliation, “the creation of a beloved community”, rather than just winning.

This was the pattern for the rest of his life as he worked to promote freedom. Freedom for black Americans from the injustices of discrimination, racism, political and economic exclusion “to take their rightful place in God’s world”. Freedom for white Americans from their imprisonment in corrosive attitudes and unjust structures. It was a spiritual as much as a political imperative, a gospel based on the power of redemption - through suffering (including non-violent conflict), and through love. In spite of imprisonment, official harassment, public vilification, being stabbed, and constantly criticised for being too radical - or not radical enough - he always kept to that gospel. In ‘Forgive Your Enemies’ he wrote:

…Jesus says, “Love your enemies.” Because if you hate your enemies, you have no way to redeem and to transform them. But if you love your enemies, you will discover that at the very root of love is the power of redemption.

The other main milestones in the life of Martin Luther King are largely well known:

- becoming head of the new Southern Christian Leadership Conference

- arrested and imprisoned in Birmingham (Alabama) for defying a court order on demonstrating

- his famous ‘I have a dream’ address in 1963 when 250,000 took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

- leading civil rights demonstrations, which helped to change attitudes and bring about the Civil Rights Act of 1964

- promoting black people’s voting rights, which contributed to the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- in 1964 receiving the Nobel Peace Prize and visiting Pope Paul VI

- his assassination in Memphis on 4 April 1968 at the age of 39, the victim of a sick and violent society

While Martin remained true to his Christian beliefs and kept faith in the Ghandi approach, not all his supporters or fellow workers were agreed. After his death the civil rights movement fragmented even more and seemed to lose its way. For many, ‘Do good to those who hate you’ became ‘Might is right’. The momentum for change slowed and slackened. Poignantly, in the hotel room where King was killed, a plaque on the wall reads:

Behold here comes the dreamer. Let us slay him, and we shall see what becomes of his dream.

We all need our heroes, just as Martin Luther King needed Ghandi. It is not easy, as his life shows us, to avoid the trap of blunting, blurring and simplifying the ideals we see in them, because life is easier that way. If we would grow we must hold fast to the dream.

More on the life and writings of Martin Luther King at Stanford University, USA

Return to the Articles contents page

http://www.stpetersnottingham.org/saints/king.html

© St Peter's Church, Nottingham

Last revised 25th March 2000