|

Seeing salvation...

...in the National Gallery

The National Gallery chose to mark the Millennium by holding an exhibition of Images of Christ. The purpose was not to present the Life of Christ in art, but to look at the way artists over the centuries had faced the difficulties of representing Jesus - as God who became man, as both human and divine, whose suffering was both personal and cosmic, who is both Shepherd and Sheep, Saviour and Sacrifice, Prince of Peace and Suffering Servant. Although grounded in items drawn from its own enormous resources, the Gallery included items from twenty-seven other lenders (mainly UK public collections) to balance the displays and broaden the time range represented. There were seven sections, with a room devoted to each: Sign and Symbol; The Dual Nature; The True Likeness; Passion and Compassion; The Saving Body; and The Abiding Presence.

There

was something to engage with, or to learn, from nearly all the works, and

only a few I found positively off-putting - such as the statue of Jesus

with his fingers deep in the open wound in his side. Some were

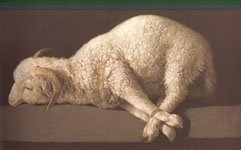

overpowering in their stark simplicity - such as Francesco de Zurbarin’s

Agnus Dei (or Bound Lamb) - a lamb on an altar with feet bound

together, innocent, trusting and helpless. Even Holman Hunt’s well known

Light of The World, which has never appealed to me, had a majestic

quality - partly from its size (over 7ft in height), partly being fresh

after cleaning.

There

was something to engage with, or to learn, from nearly all the works, and

only a few I found positively off-putting - such as the statue of Jesus

with his fingers deep in the open wound in his side. Some were

overpowering in their stark simplicity - such as Francesco de Zurbarin’s

Agnus Dei (or Bound Lamb) - a lamb on an altar with feet bound

together, innocent, trusting and helpless. Even Holman Hunt’s well known

Light of The World, which has never appealed to me, had a majestic

quality - partly from its size (over 7ft in height), partly being fresh

after cleaning.

The

earliest Christian art was all symbolic. Springing from a tradition where

the name of God was too sacred to write, it was unthinkable to portray the

person of Jesus in picture or statue for many centuries. Hence the use of

word-signs and verbal imagery - the fish, the cross, the chi-rho ‘monogram

of Christ’ and the IHS trigram, which evolved among

Christian communities in the first four centuries AD.

The

earliest Christian art was all symbolic. Springing from a tradition where

the name of God was too sacred to write, it was unthinkable to portray the

person of Jesus in picture or statue for many centuries. Hence the use of

word-signs and verbal imagery - the fish, the cross, the chi-rho ‘monogram

of Christ’ and the IHS trigram, which evolved among

Christian communities in the first four centuries AD.

Even centuries later it was technically impossible to represent imagery of Christ as light - or the Light. It was only when artists began using oil in painting in the late 15th century that it became possible to represent darkness, and this was necessary to contrast with light. A delightful nativity scene from this period Nativity at Night by Geetgen tot Sint Jans, has an infant Jesus radiating light in a dark stable, brightly illuminating the face of a very young Mary and attendant shepherds.

The

picture that held my attention for the most time, and had several return

visits, was Murillo’s Heavenly and Earthly Trinities. It has

rather conventional figures for God the Father (old man) and the Holy

Spirit (as a dove), over Jesus as a young boy with his parents on either

side. Most striking is the sheer humanity and ordinariness of both Mary

and Joseph, whose outward gaze invites the viewer to behold, and engage

with the two trinities. There is a place for us ordinary folk there. The

rather idealised boy Christ-child seems to personify a purity and

innocence for us to emulate. But he is standing on a stone which could be

an altar, a grave, or the ‘corner-stone’ over which we can stumble,

indicating perhaps the difficulty of belief in Trinitarian doctrine.

However its message of love was the most powerful, in both human and

heavenly trinities; for love cannot be complete without three dimensions -

love given to, love received from, love shared for - which is central to

my understanding of the Trinity.

The

picture that held my attention for the most time, and had several return

visits, was Murillo’s Heavenly and Earthly Trinities. It has

rather conventional figures for God the Father (old man) and the Holy

Spirit (as a dove), over Jesus as a young boy with his parents on either

side. Most striking is the sheer humanity and ordinariness of both Mary

and Joseph, whose outward gaze invites the viewer to behold, and engage

with the two trinities. There is a place for us ordinary folk there. The

rather idealised boy Christ-child seems to personify a purity and

innocence for us to emulate. But he is standing on a stone which could be

an altar, a grave, or the ‘corner-stone’ over which we can stumble,

indicating perhaps the difficulty of belief in Trinitarian doctrine.

However its message of love was the most powerful, in both human and

heavenly trinities; for love cannot be complete without three dimensions -

love given to, love received from, love shared for - which is central to

my understanding of the Trinity.

Among the many nativity and epiphany scenes was a curiously attractive, tiny, wood panel Virgin and Child. Set in a 15th century kitchen, Mary looks about to bath the baby in a bowl by the fire with a basket of towels or nappies close at hand.

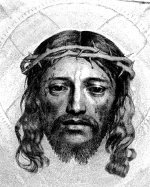

For

me the most interesting work in the True Likeness section was

Claude Mellan’s Veil of St Veronica. An impressive enough picture

from an engraving, but amazingly drawn as a single line, radiating in a

spiral from the tip of the nose but varying in width to create the image.

For

me the most interesting work in the True Likeness section was

Claude Mellan’s Veil of St Veronica. An impressive enough picture

from an engraving, but amazingly drawn as a single line, radiating in a

spiral from the tip of the nose but varying in width to create the image.

In the centre of the Passion and Compassion room was a life-sized limestone statue of Christ on a Cold Stone. Christ, naked save for a crown of thorns, sits in an attitude of inconsolable sorrow - vulnerable and waiting what is to come. It evokes responses of compassion for the sufferer and by extension all who are degraded; sorrow for the sin which is the cause; and gratitude for the loving sacrifice on our behalf. The more of humanity we see the in the life of Christ, the more closely we seem to approach the divine.

The

image that I would most like to retain is of a work that was, ironically,

not on display but represented by a picture. This is the statue Ecce

Homo by Mark Wallinger, which we saw in January when it was displayed

on the ‘empty plinth’ in Trafalgar Square. This small figure of

Christ, although nearly naked, looks a contemporary person (indeed it was

cast from a real person). Christ for today - one of us, but also separate.

He wears a crown of gold barbed wire and looks out on the world, dwarfed

by the enormous platform on which he stands. Crowded mental images form

and change, leaping from ‘Insignificant man’ to ‘Benign Overseer’

to ‘Prince of Peace’ to ‘Suffering Servant’… and back again, the

way a credit card hologram changes with the slightest movement.

The

image that I would most like to retain is of a work that was, ironically,

not on display but represented by a picture. This is the statue Ecce

Homo by Mark Wallinger, which we saw in January when it was displayed

on the ‘empty plinth’ in Trafalgar Square. This small figure of

Christ, although nearly naked, looks a contemporary person (indeed it was

cast from a real person). Christ for today - one of us, but also separate.

He wears a crown of gold barbed wire and looks out on the world, dwarfed

by the enormous platform on which he stands. Crowded mental images form

and change, leaping from ‘Insignificant man’ to ‘Benign Overseer’

to ‘Prince of Peace’ to ‘Suffering Servant’… and back again, the

way a credit card hologram changes with the slightest movement.

I’m

glad we made it to the National Gallery - it was a good day out, in spite

of the enormous queue and long wait to get in. It is a tribute to the way

the exhibition has been conceived and presented that so many people came

to see it and made it so enormously successful. It was also free - which

helped. We know from those we met and talked to that its appeal was broad

- not just to signed-up Christians or art lovers. It had something

significant and valuable for those who were ‘not religious’, those

with little or no faith - like the young lady we met on the train to

London, bumped into at the exhibition, and chatted with on the return

journey.

I’m

glad we made it to the National Gallery - it was a good day out, in spite

of the enormous queue and long wait to get in. It is a tribute to the way

the exhibition has been conceived and presented that so many people came

to see it and made it so enormously successful. It was also free - which

helped. We know from those we met and talked to that its appeal was broad

- not just to signed-up Christians or art lovers. It had something

significant and valuable for those who were ‘not religious’, those

with little or no faith - like the young lady we met on the train to

London, bumped into at the exhibition, and chatted with on the return

journey.

Why it should be so is not clear but, in addition to personal benefit from this exhibition, there is a sense of hope and encouragement that we have not as a society, completely given in to mindless, Godless, dumbed-down trivia for our leisure time. Although smaller in scale, Seeing Salvation has been in proportion very much more successful than The Dome in attracting and satisfying visitors. We can all take heart from that.

Return to the Articles contents page

http://www.stpetersnottingham.org/misc/salvation.html

© St Peter's Church, Nottingham

Last revised 4th June 2000